Year Without a Summer

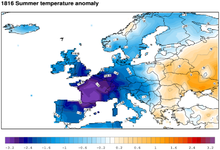

The Year Without a Summer (also known as the Poverty Year, Year There Was No Summer and Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death[1]) was 1816, in which severe summer climate abnormalities destroyed crops in Northern Europe, the Northeastern United States and eastern Canada.[2][3] Average global temperatures decreased about 0.4–0.7 °C (0.7–1.3 °F),[4] enough to cause significant agricultural problems around the globe.

Historian John D. Post has called this "the last great subsistence crisis in the Western world".[5]

Most consider the climate anomaly to have been caused by a combination of a historic low in solar activity with a volcanic winter event; the latter caused by a succession of major volcanic eruptions capped off by the Mount Tambora eruption of 1815, the largest known eruption in over 1,600 years.

Contents |

Description

The unusual climatic aberrations of 1816 had the greatest effect on the Northeastern United States, the Canadian Maritimes, Newfoundland, and Northern Europe. Typically, the late spring and summer of the northeastern U.S. and southeastern Canada are relatively stable: temperatures (average of both day and night) average about 20–25 °C (68–77 °F), and rarely fall below 5 °C (41 °F). Summer snow is an extreme rarity.

In the spring and summer of 1816, a persistent dry fog was observed in the northeastern United States. The fog reddened and dimmed the sunlight, such that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Neither wind nor rainfall dispersed the "fog". It has been characterized as a stratospheric sulfate aerosol veil.[6]

In May 1816,[7] frost killed off most of the crops that had been planted, and on 4 June 1816, frosts were reported in Connecticut, and by the following day, most of New England was gripped by the cold front. On 6 June 1816, snow fell in Albany, New York, and Dennysville, Maine.[8] Nearly a foot (30 cm) of snow was observed in Quebec City in early June, with consequent additional loss of crops—most summer-growing plants have cell walls which rupture even in a mild frost. The result was regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality.

In July and August, lake and river ice were observed as far south as Pennsylvania. Rapid, dramatic temperature swings were common, with temperatures sometimes reverting from normal or above-normal summer temperatures as high as 35 °C (95 °F) to near-freezing within hours. Even though farmers south of New England did succeed in bringing some crops to maturity, maize and other grain prices rose dramatically. The staple food oats,[9] for example, rose from 12¢ a bushel ($3.40/m³) the previous year to 92¢ a bushel ($26/m³)—nearly eight times as much. Those areas suffering local crop failures had to deal with the lack of roads in the early 19th century, preventing any easy importation of bulky food stuffs.[10]

Cool temperatures and heavy rains resulted in failed harvests in the British Isles as well. Families in Wales traveled long distances as refugees, begging for food. Famine was prevalent in north and southwest Ireland, following the failure of wheat, oat and potato harvests. The crisis was severe in Germany, where food prices rose sharply. Due to the unknown cause of the problems, demonstrations in front of grain markets and bakeries, followed by riots, arson and looting, took place in many European cities. It was the worst famine of the 19th century,[8][11]

In China, the cold weather killed trees, rice crops and even water buffalo, especially in northern China. Floods destroyed many remaining crops. Mount Tambora’s eruption disrupted China’s monsoon season, resulting in overwhelming floods in the Yangtze Valley in 1816. In India the delayed summer monsoon caused late torrential rains that aggravated the spread of cholera from a region near the River Ganges in Bengal to as far as Moscow.[12]

In the ensuing bitter winter of 1817, when the thermometer dropped to -32 °C (-26°F), the waters of New York's Upper Bay froze deeply enough for horse-drawn sleighs to be driven across Buttermilk Channel from Brooklyn to Governors Island.[13]

The effects were widespread and lasted beyond the winter. In eastern Switzerland, the summers of 1816 and 1817 were so cool that an ice dam formed below a tongue of the Giétro Glacier high in the Val de Bagnes; in spite of the efforts of the engineer Ignaz Venetz to drain the growing lake, the ice dam collapsed catastrophically in June 1818.[14]

Causes

It is now generally thought that the aberrations occurred because of the 1815 (April 5–15) volcanic Mount Tambora eruption[15][16] on the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia (then part of the Dutch East Indies). The eruption had a Volcanic Explosivity Index ranking of 7, a super-colossal event that ejected immense amounts of volcanic dust into the upper atmosphere. It was the world's largest eruption since the Hatepe eruption over 1,630 years earlier in AD 180. The fact that the 1815 eruption occurred during the middle of the Dalton Minimum (a period of unusually low solar activity) is also significant.

Other large volcanic eruptions (with VEI at least 4) during the same time frame are:

- 1812, La Soufrière on Saint Vincent in the Caribbean

- 1812, Awu on Sangihe Islands, Indonesia

- 1813, Suwanosejima on Ryukyu Islands, Japan

- 1814, Mayon in the Philippines

These other eruptions had already built up a substantial amount of atmospheric dust. As is common following a massive volcanic eruption, temperatures fell worldwide because less sunlight passed through the atmosphere.

Effects

As a result of the series of volcanic eruptions, crops in the above cited areas had been poor for several years; the final blow came in 1815 with the eruption of Tambora. In the United States, many historians cite the "Year Without a Summer" as a primary motivation for the western movement and rapid settlement of what is now western and central New York and the American Midwest. Many New Englanders were wiped out by the year, and tens of thousands struck out for the richer soil and better growing conditions of the Upper Midwest (then the Northwest Territory).

Europe, still recuperating from the Napoleonic Wars, suffered from food shortages. Food riots broke out in the United Kingdom and France and grain warehouses were looted. The violence was worst in landlocked Switzerland, where famine caused the government to declare a national emergency. Huge storms, abnormal rainfall with floodings of the major rivers of Europe (including the Rhine) are attributed to the event, as was the frost setting in during August 1816. A major typhus epidemic occurred in Ireland between 1816 and 1819, precipitated by the famine caused by "The Year Without a Summer". It is estimated that 100,000 Irish perished during this period. A BBC documentary using figures compiled in Switzerland estimated that fatality rates in 1816 were twice that of average years, giving an approximate European fatality total of 200,000 deaths.

The eruption of Tambora also caused Hungary to experience brown snow. Italy experienced something similar, with red snow falling throughout the year. The cause of this is believed to have been volcanic ash in the atmosphere.

In China, unusually low temperatures in summer and fall devastated rice production in Yunnan province in the southwest, resulting in widespread famine. Fort Shuangcheng, now in Heilongjiang province, reported fields disrupted by frost and conscripts deserting as a result. Summer snowfall was reported in various locations in Jiangxi and Anhui provinces, both in the south of the country. In Taiwan, which has a tropical climate, snow was reported in Hsinchu and Miaoli, while frost was reported in Changhua.[17]

Cultural effects

High levels of ash in the atmosphere led to unusually spectacular sunsets during this period, a feature celebrated in the paintings of J. M. W. Turner. It has been theorised that it was this that gave rise to the yellow tinge that is predominant in his paintings such as Chichester Canal circa 1828. A similar phenomenon was observed after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, and on the West Coast of the United States following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines.

The lack of oats to feed horses may have inspired the German inventor Karl Drais to research new ways of horseless transportation, which led to the invention of the Draisine or velocipede. This was the ancestor of the modern bicycle and a step towards mechanized personal transport.[18]

The crop failures of the “Year without Summer” forced the family of Joseph Smith to move from Sharon, Vermont to Palmyra, New York [19], precipitating a series of events culminating in the publication of the Book of Mormon and the founding of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[20]

In July 1816 "incessant rainfall" during that "wet, ungenial summer" forced Mary Shelley, John William Polidori and their friends to stay indoors for much of their Swiss holiday. They decided to have a contest, seeing who could write the scariest story, leading Shelley to write Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus and Polidori to write The Vampyre.[21]

The Year without a Summer also inspired Lord Byron to write his 1816 poem Darkness.

Justus von Liebig, a chemist who had experienced the famine as a child in Darmstadt, later studied plant nutrition and introduced mineral fertilizers.

Comparable events

- Toba catastrophe 70,000 to 75,000 years ago.

- The Hekla 3 eruption of about 1200 BC, contemporary with the historical bronze age collapse.

- The 1628–26 BC climate disturbances, usually attributed to the Minoan eruption of Santorini.

- Climate changes of 535–536 have been linked to the effects of a volcanic eruption, possibly at Krakatoa.

- An eruption of Kuwae, a Pacific volcano, has been implicated in events surrounding the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

- An eruption of Huaynaputina, in Peru, caused 1601 to be the coldest year in the Northern Hemisphere for six centuries (see Russian famine of 1601–1603).

- An eruption of Laki, in Iceland, caused major fatalities in Europe, 1783–84.

- The eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 led to odd weather patterns and decrease in temperatures in the United States, particularly in the Midwest and parts of the Northeast. An unusually warm winter and spring were followed by an unusually cool and wet summer in 1992.

See also

- Little Ice Age

- New England's Dark Day

- Volcanic winter

- Timetable of major worldwide volcanic eruptions

- 1816

- White Christmas in the Southern Hemisphere

Footnotes

- ↑ Weather Doctor's Weather People and History: Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death, The Year There Was No Summer

- ↑ Saint John New Brunswick Time Date

- ↑ The Quebec Chapter of the Canada Country Study Climate Impacts and Adaptation executive summary

- ↑ Stothers, Richard B. (1984). "The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath". Science 224 (4654): 1191–1198.

- ↑ Evans, Robert Blast from the Past, Smithsonian Magazine. July 2002

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). "Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815". Progress in Physical Geography 27 (2): 230–259

- ↑ Weather Doctor's Weather People and History: Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death, The Year There Was No Summer

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Oppenheimer 2003

- ↑ Oats are a necessary staple in an economy dependent upon horses for primary transportation.

- ↑ John Luther Ringwalt, Development of Transportation Systems in the United States, "Commencement of the turnpike and bridge era", 1888:27 notes that the very first artificial road was the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, 1792-95, a single route of 62 miles; " it seems impossible to ascribe to the turnpike movement in the years before 1810 any significant improvement in the methods of land transportation in southern New England, or any considerable reduction in the cost of land carriage" (Percy wells Bidwell, "Rural economy in New England", in Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of arts and Sciences, 20 [1916:317]).

- ↑ "The 'year without a summer' in 1816 produced massive famines and helped stimulate the emergence of the administrative state", observes Albert Gore, Earth in the Balance: ecology and the human spirit, 2000:79

- ↑ Discovery Extreme Earth

- ↑ Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (Oxford University Press) 1999:494.

- ↑ The flood is fully described in Jean M. Grove, Little Ice Ages, Ancient and Modern (as The Little Ice Age 1988) rev. ed. 2004:161.

- ↑ Indo Digest

- ↑ Bellrock.org.uk : Misc

- ↑ http://www.igsnrr.ac.cn/lwzzImg/1161151232919.pdf

- ↑ "Brimstone and bicycles - 29 January 2005 - New Scientist"

- ↑ moved in 1816

- ↑ Discovery Channel, "Extreme Earth"

- ↑ Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. Random House. pp. XV–XVI. ISBN 0-679-60059-0.

Additional reading

- BBC Timewatch documentary: Year Without Summer, Cicada Films (BBC2, 27 May 2005)

- Willie Soon and Steven H.Yaskell:Year without a Summer, Vol. 32, # 3 May / June, Mercury (Astronomical Society of the Pacific) 2003

- Hans-Erhard Lessing: Automobilitaet: Karl Drais und die unglaublichen Anfaenge, Leipzig 2003

- Henry & Elizabeth Stommel: Volcano Weather: The Story of 1816, the Year without a Summer, Seven Seas Press, Newport RI 1983 ISBN 0-915160-71-4

- The Story of the Year of Cold, by Dozier, Lou Zerr Press, 2009